e-learning centre on sustainable development

CASE STUDIES IN SUSTAINABILITY

Urban Nature Centre

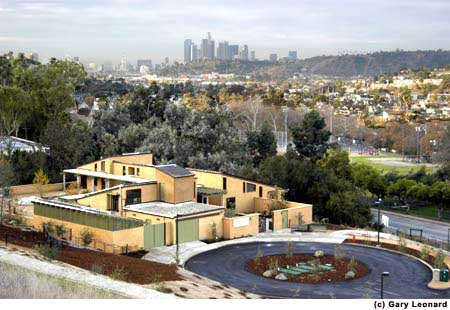

Audubon Center at Debs Park

Urban Oasis Magazine, March 2004

Written by Dan Koeppel

Background: East Los Angeles is one of the most economically deprived areas in Los Angeles. It has a very high crime rate, gang violence, and poor quality schools, offering little hope for future generations.

Debs Park. Tucked between the Pasadena Freeway and the northeastern neighborhoods of East Los Angeles, the park's centerline is a well-pitched ridge, 500 feet high. Debs Park's eastern half has always been busy, with playgrounds, parking lots, and an occasional petting zoo. But its western side has seen little use since opening in 1952. Initially, it hosted soapbox derbies; more recently its secluded lower reaches became a haunt of prostitutes. The area's loneliness had allowed it to grow wild. Today the last stands of coastal sage in this part of Los Angeles survive amid patches of black walnut, blue elderberry, and toyon; snakes, lizards, rabbits, and coyotes move through the firebreaks.

Elsa Lopez stepped out of her office at the Audubon center, where she serves as the director. "I was lucky enough to be able to do this when I was younger," she says. "Most people who grew up around here haven't had that opportunity." For Lopez and her eight brothers and sisters, Debs Park provided a steady exposure to nature. She gestures toward the slope. "We'd walk up this same hill," Lopez says with a sense of mischief, "and slide down on cardboard boxes."

While there won't be any scheduled carton surfing at the refurbished Debs Park, Lopez's mission hinges upon today's neighborhood kids having as much fun on the hillside as she did. Debs Park may offer them their only chance to feel the soft earth of a hiking trail instead of the hard pavement of a sidewalk. The surrounding neighborhoods of Highland Park and Boyle Heights are the city's most crowded; the population density, at more than 25,000 people per square mile, is nearly four times the average citywide. More than half of local households consist of four or more people. Ninety-four percent of the residents in Boyle Heights are Latino.

A lack of facilities has certainly limited the community's opportunities for outdoor recreation. But so have time and money. In many families both parents work—often several jobs. Median incomes are low, less than $20,000 in one neighborhood close to the center.

From the top of the hill, the surrounding area appears as a thickly built patchwork—highways and railroads, freight yards, and street after street of low-slung houses, schools, and churches. The most surprising aspect of the view, though, is that it exists at all. Over the years investment has tilted toward the city's well-heeled west side; hilltops have been leveled and transformed into everything from museums (like the Getty Center, built in the Santa Monica Mountains) to planned communities and shopping malls. With the city's east side largely ignored, Debs Park escaped the pressures that might otherwise have caused it to vanish. The irony isn't lost on Lopez: "We were forgotten so long we were practically untouched. The park was a blank slate."

Building a nature center in the community seemed like a great idea—something nobody could object to. "The problem," Lopez explains, "is that we get plenty of 'great ideas' around here." One of those was a toxin-spewing incinerator project, posing as a jobs program, proposed for a residential neighborhood. Lopez helped to successfully fight the incinerator in 1987, when she was involved with Mothers of East Los Angeles, an activist group her own mother helped found in order to prevent a prison from being built just a few blocks from Debs Park.

Under such circumstances, credibility arrives slowly. For two years Ingalls attended community meetings and talked to everyone she could. Michael Perez, a computer programmer who lives just across the street, was one of the first in the neighborhood to be won over. Like Lopez, Perez had grown up playing in Debs Park; when he heard about Audubon's plan, he rushed to the storefront. Proposals to remove graffiti and refurbish the park's hiking trails sounded great, he says, but what really convinced him were plans to restore the 282-acre facility's habitat. "That's what's going to get people's hands in the dirt and give them something to cherish," he says.

The project will begin with native plants, which neighborhood kids will help grow in the center's Children's Woodland.

One by one, people who loved the park, feared it, or didn't even know it existed started to accept the idea.

At the grand opening, a young boy—wearing a backpack filled with an insect net, a magnifying glass, and watercolor paints (kids can borrow them from Audubon as they enter)—knelt near a tiny pond, staring at dragonflies. The boy's grandmother stood a few feet away, smiling, watching quietly. She came from Mexico in the 1960s and is one of Gonzalez's street-corner converts. I am introduced, but the woman is too modest to give her name, offering only a simple, nostalgic recollection: "When I was a girl, I knew the name of every bird."

Vivid but faded memories of nature draw the elderly to Debs Park, where 138 species of birds thrive. And, as this woman knows, there's also joy in witnessing the discoveries of youth. Multiple generations of a single family will often visit Debs Park together; it has become a welcome challenge for the center to design programming that spans all ages.

A recent Los Angeles Times editorial celebrated Debs Park: ". . . once you're through the black iron gates embellished with hummingbirds and butterflies, the bustling natural world comes into focus." Park visitors go on nighttime hikes to learn about astronomy; they take painting classes, learn how to cook native plants, and hear stories told by descendants of the area's Gabrielino Indians. "Fifty thousand children live within two miles, many of them part of poor working families along the city's gritty industrial edge," the editorial continued. "The park itself has long been an underused jewel."

For years Lopez has been taking local kids—many of them gang members who've spent time in youth incarceration facilities—on camping trips. She's seen what nature does: "It scares them. Then they let their guard down. They become kids again." Instead of regarding one another with tough suspicion, they actually begin playing.

Taking every schoolchild in East Los Angeles camping is impossible. Bringing each one to Debs Park? That's doable.

When I asked about teenagers, Lopez told me about a 17-year-old named Juan. He'd been trying hard to keep out of gangs, so he had decided to join the Marine Corps, or maybe go into law enforcement. I didn't think much about this until, on a recent park visit, I watched a young volunteer in a red T-shirt. He had the close-cropped hair and baggy pants that are a uniform for many of the city's high school kids; there was a trace of mustache above his lip. He was showing a gopher snake to visitors—handling it gently but with a sort of macho "look at me with the snake" demeanor. He explained to me that he'd agreed to work at the park only so he could spend more time with his girlfriend, who was also a volunteer. But over time he had come to love it there, even though he had never experienced anything like it.

"I thought nature was someplace dangerous, almost," he said, before launching into a brilliant, teens-only explanation of the importance of understanding the outdoors: "Going to a concert is great, but it's even better when you know who's playing and what the songs are called." When I asked about his ambitions, I realized he was the young man Lopez had mentioned. He talked about the military and the police, and why those career choices attracted him: "Protecting people," he said. "But," he added tentatively, "there are other ways to protect." His eyes widened a bit, as if trying out the idea before actually speaking it, to see if it fit. "Maybe," he said, "if I protect nature, that's a way to protect people, too."

At first glance, the Audubon Center at Ernest E. Debs Park may not look like one of the greenest buildings in America. Visitors can't see the solar panels that, lying flat against the roof, power the building and everything in it. Though the toilets flush with water treated on-site, and use half the water of the most efficient models, the bathrooms appear perfectly standard.

But look closer. Nearly every item a visitor encounters in the nature center—cabinets made of crushed sunflower seeds, linoleum counters recycled from old tires, carpet fibers extracted from the Mexican agave plant—is in fact made from sustainable resources.

The Debs Park center is the first building in the country to receive the U.S. Green Building Council's Platinum Rating under its new rating system—the highest possible award from the nation's leading authority on sustainable building practices. Earning this distinction wasn't easy. To start with, more than 50 percent of the building materials were locally manufactured, and more than 90 percent of the construction debris created was then recycled. The structure's concrete consists of fly ash recycled from the burning of coal; the steel rebar within the concrete is made from melted-down firearms, obtained from a trade-in program run by the city of Los Angeles.

Designed to ease pressure on water- and energy-stressed California, the Debs Park nature center functions entirely off the sewer and power grid—the first public building in Los Angeles to do so. Its location has been calculated to take advantage of ventilation, helped along by high-efficiency fans. Exposed interior walls keep the temperature moderate; solar-powered heating and cooling systems kick in only when necessary. Windows provide maximum natural light and efficient insulation.

Walk through the center's doors and you'll find a courtyard that's been equally well-thought-out. Western sycamores shade the building, and California grape shades an arch leading to the Children's Woodland. A recirculating, solar-powered fountain offers a respite to wildlife. A few steps farther and a sustainably certified wooden tower offers a view of the children's garden, which highlights native plant communities as they change throughout the seasons. By experiencing the Audubon Center at Debs Park, visitors big and small can take home an important lesson about living in balance with the local environment. After all, says the center's director, Elsa Lopez, the building should not just be one you learn in, but learn from.

Guide Questions

Identify and explain all social, economic and environmental principles

Analyze the project in the context of "systems thinking"

Draw a diagram showing the connection between various parts of the system

Paper from the IEF Orlando Workshop 2004

Return to Case Studies page

Return to e-learning centre

Last updated 12 April 2006