Newsletter of the

INTERNATIONAL ENVIRONMENT FORUM

Volume 20, Number 10 --- 15 October 2018

Website: iefworld.org

Article submission: newsletter@iefworld.org Deadline next issue 13 November 2018

Secretariat Email: ief@iefworld.org General Secretary

Postal address: 12B Chemin de Maisonneuve, CH-1219 Chatelaine, Geneva, Switzerland

Download the pdf version

From the Editor, Request for information for upcoming newsletters

This newsletter is an opportunity for IEF members to share their experiences, activities, and initiatives that are taking place at the community level on environment, climate change, and sustainability. All members are welcome to contribute information about related activities, upcoming conferences, news from like-minded organizations, recommended websites, book reviews, etc. Please send information to newsletter@iefworld.org.

Please share the Leaves newsletter and IEF membership information with family, friends and associates, and encourage interested persons to consider becoming a member of the IEF.

IEF Governing Board Election

In the recent election of the International Environment Forum Governing Board for 2018-2019, the following members were chosen: Arthur Dahl (Switzerland), Sylvia Karlsson-Vinkhuyzen (Netherlands), Laurent Mesbah (Bosnia & Herzegovina), Wendi Momen (United Kingdom), Christine Muller (USA), Victoria Thoresen (Norway), and Halldor Thorgeirsson (Iceland).

A total of 49 members voted during the election. The board welcomes Halldor as its newest member. Halldor has recently retired from a senior position in the Secretariat of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change.

Tepa Suaesi

IEF member Tofilau Tepa Suaesi (1960-2017) has passed away in Samoa. Tepa was an Environmental Officer of the Secretariat of the Pacific Regional Environment Programme (SPREP) responsible for coordinating the organization's programmes for the monitoring, evaluation and reporting of the state of the environment in the Pacific Island Countries and the region as a whole. [SPREP was organized 35 years ago by IEF president Arthur Dahl.] Tepa was also a member of the governing board of Samoa's national environment nongovernmental organization 'O le Si'osi'omaga Society Inc. which helps grassroots communities in conservation and other natural resources management activities. Before joining the staff of SPREP he was an employee of the Government of Samoa in the Ministry of Natural Resources & Environment responsible for environment education, information and training, and terrestrial biodiversity programmes. Tepa was also longtime Secretary of the National Spiritual Assembly of the Baha’is of Samoa.

Global Warming of 1.5 °C - The IPCC Special Report

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has issued its special report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty.

As a consensus document of scientists and governments, it is moderate in tone, but it nevertheless shows that urgent action by everyone, from governments at all levels to businesses and every individual will be required to head off what could best be described as a looming climate catastrophe. The climate is changing faster than previously expected, with impacts already evident now with 1°C of warming. We could reach 1.5°C of warming as early as 2030 with some further impacts in heatwaves, floods, droughts and biodiversity loss that cannot be avoided. A target of 2°C is no longer considered safe, and present commitments under the Paris Agreement would take the planet to at least 3°C. The next few years will be critical to our future.

At the same time, the report has positive things to say. If we act now with the necessary urgency, it is not yet too late. We know what to do, and have the necessary technologies. The transition will be good for the economy and create jobs. While it will be expensive, it will cost less than the damage from not doing enough.

The report also relates its findings to the Sustainable Development Goals, and shows that responding now to climate change will also help to meet the goals, reduce poverty, and move the planet towards sustainability.

The following is an edited version of the main headline statements from the IPCC report.

Understanding Global Warming of 1.5°C

Human activities are estimated to have caused approximately 1.0°C of global warming above pre-industrial levels, with a likely range of 0.8°C to 1.2°C. Global warming is likely to reach 1.5°C between 2030 and 2052 if it continues to increase at the current rate.

Warming from anthropogenic emissions from the pre-industrial period to the present will persist for centuries to millennia and will continue to cause further long-term changes in the climate system, such as sea level rise, with associated impacts, but these emissions alone are unlikely to cause global warming of 1.5°C.

Climate-related risks for natural and human systems are higher for global warming of 1.5°C than at present, but lower than at 2°C. These risks depend on the magnitude and rate of warming, geographic location, levels of development and vulnerability, and on the choices and implementation of adaptation and mitigation options.

Projected Climate Change, Potential Impacts and Associated Risks

Climate models project robust differences in regional climate characteristics between present-day and global warming of 1.5°C, and between 1.5°C and 2°C. These differences include increases in: mean temperature in most land and ocean regions, hot extremes in most inhabited regions, heavy precipitation in several regions, and the probability of drought and precipitation deficits in some regions.

By 2100, global mean sea level rise is projected to be around 0.1 metre lower with global warming of 1.5°C compared to 2°C. Sea level will continue to rise well beyond 2100, and the magnitude and rate of this rise depends on future emission pathways. A slower rate of sea level rise enables greater opportunities for adaptation in the human and ecological systems of small islands, low-lying coastal areas and deltas.

On land, impacts on biodiversity and ecosystems, including species loss and extinction, are projected to be lower at 1.5°C of global warming compared to 2°C. Limiting global warming to 1.5°C compared to 2°C is projected to lower the impacts on terrestrial, freshwater, and coastal ecosystems and to retain more of their services to humans.

Limiting global warming to 1.5°C compared to 2ºC is projected to reduce increases in ocean temperature as well as associated increases in ocean acidity and decreases in ocean oxygen levels. Consequently, limiting global warming to 1.5°C is projected to reduce risks to marine biodiversity, fisheries, and ecosystems, and their functions and services to humans, as illustrated by recent changes to Arctic sea ice and warm water coral reef ecosystems.

Climate-related risks to health, livelihoods, food security, water supply, human security, and economic growth are projected to increase with global warming of 1.5°C and increase further with 2°C.

Most adaptation needs will be lower for global warming of 1.5°C compared to 2°C. There are a wide range of adaptation options that can reduce the risks of climate change. There are limits to adaptation and adaptive capacity for some human and natural systems at global warming of 1.5°C, with associated losses. The number and availability of adaptation options vary by sector.

Emission Pathways and System Transitions Consistent with 1.5°C Global Warming

In model pathways with no or limited overshoot of 1.5°C, global net anthropogenic CO2 emissions decline by about 45% from 2010 levels by 2030, reaching net zero around 2050. For limiting global warming to below 2°C, CO2 emissions are projected to decline by about 20% by 2030 in most pathways and reach net zero around 2075. Non-CO2 emissions in pathways that limit global warming to 1.5°C show deep reductions that are similar to those in pathways limiting warming to 2°C.

Pathways limiting global warming to 1.5°C with no or limited overshoot would require rapid and far-reaching transitions in energy, land, urban and infrastructure (including transport and buildings), and industrial systems. These systems transitions are unprecedented in terms of scale, but not necessarily in terms of speed, and imply deep emissions reductions in all sectors, a wide portfolio of mitigation options and a significant upscaling of investments in those options.

All pathways that limit global warming to 1.5°C with limited or no overshoot project the use of carbon dioxide removal (CDR) on the order of 100–1000 GtCO2 over the 21st century. CDR would be used to compensate for residual emissions and, in most cases, achieve net negative emissions to return global warming to 1.5°C following a peak. CDR deployment of several hundreds of GtCO2 is subject to multiple feasibility and sustainability constraints. Significant near-term emissions reductions and measures to lower energy and land demand can limit CDR deployment to a few hundred GtCO2 without reliance on bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS).

Strengthening the Global Response in the Context of Sustainable Development and Efforts to Eradicate Poverty

Estimates of the global emissions outcome of current nationally stated mitigation ambitions as submitted under the Paris Agreement would lead to global greenhouse gas emissions in 2030 of 52–58 GtCO2eq yr-1. Pathways reflecting these ambitions would not limit global warming to 1.5°C, even if supplemented by very challenging increases in the scale and ambition of emissions reductions after 2030. Avoiding overshoot and reliance on future large-scale deployment of carbon dioxide removal (CDR) can only be achieved if global CO2 emissions start to decline well before 2030.

The avoided climate change impacts on sustainable development, eradication of poverty and reducing inequalities would be greater if global warming were limited to 1.5°C rather than 2°C, if mitigation and adaptation synergies are maximized while trade-offs are minimized.

Adaptation options specific to national contexts, if carefully selected together with enabling conditions, will have benefits for sustainable development and poverty reduction with global warming of 1.5°C, although trade-offs are possible.

Mitigation options consistent with 1.5°C pathways are associated with multiple synergies and trade-offs across the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). While the total number of possible synergies exceeds the number of trade-offs, their net effect will depend on the pace and magnitude of changes, the composition of the mitigation portfolio and the management of the transition.

Limiting the risks from global warming of 1.5°C in the context of sustainable development and poverty eradication implies system transitions that can be enabled by an increase of adaptation and mitigation investments, policy instruments, the acceleration of technological innovation and behaviour changes.

Sustainable development supports, and often enables, the fundamental societal and systems transitions and transformations that help limit global warming to 1.5°C. Such changes facilitate the pursuit of climate-resilient development pathways that achieve ambitious mitigation and adaptation in conjunction with poverty eradication and efforts to reduce inequalities.

Strengthening the capacities for climate action of national and sub-national authorities, civil society, the private sector, indigenous peoples and local communities can support the implementation of ambitious actions implied by limiting global warming to 1.5°C. International cooperation can provide an enabling environment for this to be achieved in all countries and for all people, in the context of sustainable development. International cooperation is a critical enabler for developing countries and vulnerable regions.

IPCC. 2018. Global Warming of 1.5°C (SR15), Special Report. Summary for Policy Makers. Geneva: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, October 2018. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/sr15/

UN climate panel says ‘unprecedented changes’ needed

to limit global warming to 1.5°C

The IPCC, the United Nations top climate panel, issued the report from Incheon, Republic of Korea, where for the past week, hundreds of scientists and government representatives have been pouring over thousands of inputs to paint a picture of what could happen to the planet and its inhabitants with global warming of 1.5°C (or 2.7 degrees Fahrenheit).

“One of the key messages that comes out very strongly from this report is that we are already seeing the consequences of 1°C of global warming through more extreme weather, rising sea levels and diminishing Arctic sea ice, among other changes,” said Panmao Zhai, Co-Chair of one of the IPCC Working Groups.

The landmark Paris Agreement adopted in December 2015 by 195 nations at the 21st Conference of the Parties to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) included the aim of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change by “holding the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above preindustrial levels and pursuing efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels.”

Tweeting shortly after the report was launched UN Secretary-General António Guterres said that it is not impossible to limit global warming to 1.5°C, according to the report. But it will require unprecedented and collective climate action in all areas. There is no time to waste.

Half a degree is a big deal

The report highlights a number of climate change impacts that could be avoided by limiting global warming to 1.5°C compared to 2°C, or more.

For instance, by 2100, global sea level rise would be 10 cm lower with global warming of 1.5°C compared with 2°C.

The likelihood of an Arctic Ocean free of sea ice in summer would be once per century with global warming of 1.5°C, compared with at least once per decade with 2°C.

Moreover, coral reefs, already threatened, would decline by 70-90 percent with global warming of 1.5°C, whereas virtually all (> 99 percent) would be lost with 2°C, according to the report.

“Every extra bit of warming matters, especially since warming of 1.5°C or higher increases the risk associated with long-lasting or irreversible changes, such as the loss of some ecosystems,” said Hans-Otto Pörtner, Co- Chair of IPCC Working Group II.

‘Possible with the laws of chemistry and physics,’ but we need to move faster

“Limiting warming to 1.5°C is possible within the laws of chemistry and physics but doing so would require unprecedented changes,” said Jim Skea, Co-Chair of IPCC Working Group III.

With that in mind, the report calls for huge changes in land, energy, industry, buildings, transportation and cities. Global net emissions of carbon dioxide would need to fall by 45 per cent from 2010 levels by 2030 and reach "net zero" around 2050.

Allowing the global temperature to temporarily exceed or ‘overshoot’ 1.5ºC would mean a greater reliance on techniques that remove CO2 from the air to return global temperature to below 1.5°C by 2100.

But the report warns that “the effectiveness of such techniques are unproven at large scale and some may carry significant risks for sustainable development.”

“Limiting global warming to 1.5°C compared with 2°C would reduce challenging impacts on ecosystems, human health and well-being, making it easier to achieve the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs),” said Priyardarshi Shukla, Co-Chair of IPCC Working Group III, referring to the 17 Goals adopted by UN Member States three years ago to protect the planet and ensure that all people enjoy peace and prosperity by 2030.

The new report will feed into a process called the ‘Talanoa Dialogue,’ in which parties to the Paris accord will take stock of what has been accomplished over the past three years. The dialogue will be a part of the next UNFCCC conference of States parties, known by the shorthand COP 24, which will meet in Katowice, Poland, this December.

The IPCC press conference about the report contains a 19 min. presentation by the panel, followed by a Q&A session. The press conference starts at about the 9 min. mark: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=12S3dKrxj7c&feature=youtu.be

Six Baha’i Environmentalists Arrested

On 25. September, IranWire.com published the following article covering the arrests of six Baha'i environmentalists. The article also provides a wider background of the general persecution of environmentalists in Iran that started about half a year ago.

https://iranwire.com/en/features/5557

In the latest in a series of crackdowns on environmental activists in Iran, six people have been arrested in Shiraz. The Intelligence Ministry detained Sudabeh Haghighat, Noora Pourmoradian, Elaheh Samizadeh, Ehsan Mahboub Rahvafa, Navid Bazmandegan and his wife Bahareh Ghaderi on September 15 and 16.

In the past, it has been routine for the Revolutionary Guards’ Intelligence Agency to prosecute, arrest and interrogate environmental activists, but because the activists are Baha’is, this time the arrests were conducted by the Intelligence Ministry, which is responsible for matters regarding the religious minority.

Among the six arrests, the case of married couple Navid Bazmandegan and Bahareh Ghaderi has stood out and commanded the greatest media attention. According to Iran Human Rights Monitor (HRM), after agents searched their home, they took the pair to an unknown location, despite the fact that their five-year-old daughter Darya is suffering from cancer and still needs their care posttreatment.

The charges against the six detainees remain unknown. A wave of arrests targeting environmentalists started about six months ago. Since then, more than 50 people have been arrested. At the time of the first arrests, Isa Kalantari, the head of Iran’s Environmental Protection Agency, announced that President Rouhani had appointed a panel of four, including ministers of justice, the interior and intelligence, as well as his own deputy in legal affairs, to investigate the arrests.

But in the end not much has been accomplished. The panel announced that it had found no reason for the arrests and “naturally,” it said, the detained would be released soon. This has been the only action Rouhani’s administration has taken to protect the environmentalists so far.

“Suicide” in Prison

Kavous Seyed Emami, a notable Iranian sociologist, university professor and environmentalist, was arrested on January 24, 2018, and died in suspicious circumstances in prison two weeks later. Authorities stated that he had committed suicide but offered no convincing evidence for their claim. Instead, they banned his wife Maryam Mombini from traveling abroad.

The Revolutionary Guards’ Intelligence Agency has announced that the arrested environmentalists had been charged with “espionage,” “stealing important military information” and “taking pictures with professional cameras and sending them to the enemies” of the Islamic Republic. None of these charges have been proven and, in addition to Isa Kalantari, even Rouhani’s intelligence minister has denied the charges are applicable to the arrested environmentalists.

Isa Kalantari told the press that the cameras the Revolutionary Guards claim had been used for espionage are not suitable for recording anything accurately beyond 20 meters, saying that they cannot “even distinguish between a camel and a cheetah.” Following this, Tehran’s prosecutor, Abbas Jafari Dowlatabadi, criticized Kalantari for interfering in the affairs of the judiciary and accused him of lacking enough information.

Office of Supreme Leader Refuses to Help

Following the disagreement between the two officials, the families of the arrested environmentalists wrote a letter to the office of the Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamenei, expressing their disbelief at the charges that had been brought, and asking him to ensure that the detained would be treated justly. But Khamenei’s office brushed them off. “This case belongs to the judiciary and this office cannot interfere,” it stated.

The latest reports indicate that, in addition to the six who were arrested in Shiraz, at least eight of the arrested environmentalists are still in prison. According to Mohammad Hossein Aghasi, the lawyer for two of them, the investigation phase of the case is over and the detainees have maintained their innocence. Nevertheless, they remain behind bars and there is no news of their release.

Not long ago, in an interview with the Islamic Republic News Agency (IRNA), Isa Kalantari again quoted Intelligence Minister Mahmoud Alavi as saying that the arrested environmentalists were not spies and that their cases would be decided by the end of the summer, although none of them had been officially indicted. Following this, Gholamhossein Mohseni Ejei, the judiciary spokesman, told a news conference that five of the detained had been indicted and their case has been sent to court.

The ongoing inconsistencies between the Intelligence Ministry and the Revolutionary Guards’ Intelligence Agency, the suspicious death of Seyed Emami, the impotence of the Rouhani government (which used to boast that it was a proenvironment administration), and the unwillingness of the Supreme Leader’s office to involve itself, have fanned further worries about the fate of the jailed activists. And now six more have been arrested, and could face even harsher treatment. The six are not only environmentalists, but also Baha’is — and under the Islamic Republic, being a Baha’i is enough to be found guilty of a range of crimes. Being environmentalists on top of this will not help make their situation any easier.

Man of the Trees - Book Review

Hanley, Paul. 2018. Man of the Trees: Richard St. Barbe Baker, the first global conservationist

Regina, Saskatchewan: University of Regina Press, 300 p.

book review by Arthur Dahl

There are unsung heroes or ancestors of the environment and sustainability movement that need to be rediscovered and honoured for their foresight. One is Alexander von Humboldt (1769-1859) (see book review by Dahl 2016). Another is Richard St. Barbe Baker (1889-1982). Now, IEF member Paul Hanley has written the definitive biography of St. Barbe, as he preferred to be known, published in Canada in October 2018.

Paul met St. Barbe and some of his close friends, and had access to his archives, and has pulled together all these sources to trace the amazing life and significance of St. Barbe, forester, indefatigable speaker and author, world traveller and Bahá’í. It is an unforgettable read. The book includes a foreword by HRH the Prince of Wales and an introduction by Jane Goodall.

Hanley provides detailed documentation to show how St. Barbe deserves to be called the first global conservationist. “Since his time in Africa in the early 1920s he had recognized the great danger of environmental destruction, that humankind was destroying the earth, thus threatening its future. He saw and described the future of Africa blighted by desertification and drought; envisioned the need for sustainable development far in advance of the spirit of the 1987 Brundtland Report; foresaw the Third World fuel wood crisis; grasped the global character of environment and development and the need for concerted action at the international level; understood the effect of forests on climate, thought at the time to be nonsense; foregrounded the issue of conserving biodiversity; and promoted the intrinsic value of trees and forests above and beyond any economic consideration” (p. 153).

Baker was born in England, educated on the Canadian frontier and at Cambridge, wounded in World War I, and joined the Colonial Service as a forester in Kenya, where he co-founded Men of the Trees (now the International Tree Foundation) in 1922 to incite the Kikuyu to reforest their land. He came to appreciate the wisdom of indigenous peoples in protecting the land and forest, and was expelled from the Colonial Service for interposing himself and taking a blow intended for an African.

He went on to develop techniques for sustainable forest yield in Nigeria; initiated the reforestation of Palestine, where the Guardian of the Baha’i Faith, Shoghi Effendi, became the first life member of Men of the Trees in 1929; worked for many years to conserve the redwoods of California; supported reforestation and desertification control in Australia and New Zealand; aided the Chipko “tree hugger” movement in the Himalayas; and organized a series of World Forestry Charter Gatherings in London to build diplomatic support for forest conservation. Reversing the desertification in the Sahara desert became his preoccupation, leading a expedition across the desert, and later all around its circumference, and proposing a Green Front to hold it back, which many years later is now being realised. He was infinitely practical, always planting trees and carrying seeds in his pockets, while appreciating the importance of the spiritual. He gave thousands of talks to conferences and school children, met heads of state and the Pope, received an OBE from Queen Elizabeth, and never stopped working for trees until his passing at the age of 92.

As Hanley has put it so well: “Baker had an inherent sense of world citizenship, feeling equally at home in Africa, the Middle East, the Americas, the Antipodes, Asia, and Europe, through all of which he had travelled and many parts of which he knew intimately. To this universalism was added his powerful sense of the oneness of life, a natural understanding of the interrelationships and interdependence of a global ecosphere. He knew instinctively that peace and unity were linked to a right relationship to the earth, to the land and its forests. Fed by his biblical background, his adopted Bahá’í faith, and his training in forest ecology, a vision took shape, a prophetic vision of a great, global enterprise to restore the damaged earth as a vehicle for the unification of humankind. The biblical vision of the end times, of peace and harmony in an agrarian society, of the desert blooming, of spears beat into pruning hooks, loomed large in his mind.” (p. 152)

Everyone interested in conservation, environment, sustainability and forestry, or just lovers of trees, needs to read this book and be inspired by what one person can accomplish for the planet in a lifetime.

Religion/Water/Climate: Changing Cultures and Landscapes

13-16 June 2019. Hosted by University College Cork. Cork, Ireland

Proposal Deadline: 14 December 2018 Submit your Proposal Call for Papers: Download Cork CFP

https://www.issrnc.org/conferences/2019-conference/cork-cfp/

Note: The ISSRNC is trying an experimental online session format for the 2019 conference, which has a slightly different CFP. The application below for submitting a proposal is the same, but the instructions and requirements are different for the online session, as noted in the CFP.

The ISSRNC welcomes papers, panels, and proposals from all disciplines that address the intersections of religion, nature, and culture. For this conference we especially welcome proposals that focus on religious and cultural responses to and conceptions of climate weirding, especially concerning water and climate change. The anthropogenic destabilization of global climate systems elicits responses from religious actors, but also precipitates religious questions. Of particular interest are places, ecosystems, and environmental processes where climate-induced hydrological changes have religious ramifications: coastal communities, desertification, wetlands, sea level rise, erratic rainfall, melting permafrost and glaciers, intensifying tropical storms, mangroves, fishing and fishermen, etc. By partnering with our hosts at the University College Cork, the ISSRNC seeks to advance conversations about the interconnections between water, climate, religion, and culture.

This conference advances the ISSRNC’s mission to “promote critical, interdisciplinary inquiry into the relationships among human beings and their diverse cultures, environments, and religious beliefs and practices.” At this conference, we hope to develop linkages between scholars of religion and other fields in the environmental humanities and social sciences that explore human ecology in its cultural complexity, critically engaging the patterns of social, economic, and religious organization that precipitate environmental degradation and identify emerging alternatives.

We seek papers and pre-arranged panel sessions from all disciplines that focus on the following thematic areas. In addition, we welcome any papers or panels addressing the nexus of religion, nature, and culture.

• The religious, social, philosophical, cultural, and spiritual implications of the impact of climate change on coastlines, wetlands, mangroves, melting permafrost and glaciers, rising sea levels, erratic rainfall, desertification, intensifying tropical storms, fishing, shipping, and water-based forms of tourism and pilgrimage

• Religious responses to climate change (e.g. theology, advocacy, activism, and adaptation)

• Religious and spiritual conceptions of water and activities and beliefs concerning sacred waters, such as rivers, springs and holy wells

• The impact of climate disruption on the movement of human and other-than-human beings; species migration, climate refugees and migrants

• The moral and mythic significance of climate related biodiversity loss and extinction

• Questions concerning ecological aesthetics, environmental ethics, planetary consciousness, and biological ontologies

• Cultures of resilience, in history, in practice, and in our imaginations

• The intersection of climate change, economic inequality, and gender justice

• Water security and environmental justice

• The consequences of climate change on human rights issues

• Climate change as it relates to religion and environmental racism

• The role and impact of public scholarship related to religion and climate change

Proposals and Deadlines

Paper proposals must include two documents: The first should be a 150-word abstract that includes the Title, as well as the name and contact information of the Participant. The second should be a 500-word (or less) description of the paper that includes the title, and indicates the methods, argument, and findings as well as the relevant literature engaged. Session proposals should include paper proposals for each participant as well as an overview document describing the session title, theme, participants, and order of presentation. Proposals for sessions or events that would not fit the traditional session format are also encouraged. For instance, we invite proposals for an experimental online session that would enable ISSRNC members to present at the conference without physically attending. This session would consist of pre-recorded video presentations that would be available to all conference participants. The presenters would be expected to participate in an asynchronous online discussion of the presentation throughout the conference. We also plan to reserve space for a number of panels developed through new or existing ISSRNC online working groups. Please use the submission form below to submit your proposal by 14 December 2018.

Papers will be anonymously peer-reviewed by an international scholarly committee and decisions made by late January 2019.

All presenters must be members in good standing of the International Society for the Study of Religion, Nature and Culture by 1 April 2019. All scholars interested in religion, nature and culture are encouraged to support the Society. Presenters and session organizers are encouraged to submit their articles for publication, or their sessions for special issues, to the official publication of the ISSRNC, the Journal for the Study of Religion, Nature, and Culture (JSRNC).

What genuine ambition on climate change would look like

By David Roberts@drvox david@vox.com Updated 8 October 2018

What would it take to really tackle climate change? No delays, no gimmicks, no loopholes, no shirking of responsibility — the real thing. What would it look like?

To answer that question, it helps to understand the upper threshold of climate ambition. The target agreed upon by the world’s nations in Paris in 2015 is global warming of “well below” 2 degrees Celsius, with goodfaith efforts to hold temperature rise to 1.5 degrees.

Countries are not moving anywhere near fast enough to hit those targets, so we are currently on track for somewhere around 3 degrees. It is generally agreed that hitting 2 degrees would be quite ambitious, while hitting 1.5 would be nothing short of miraculous. Yet the scientists at the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, in their latest report, are pleading with the world to go for it, because at this point, every fraction of a degree of warming matters.

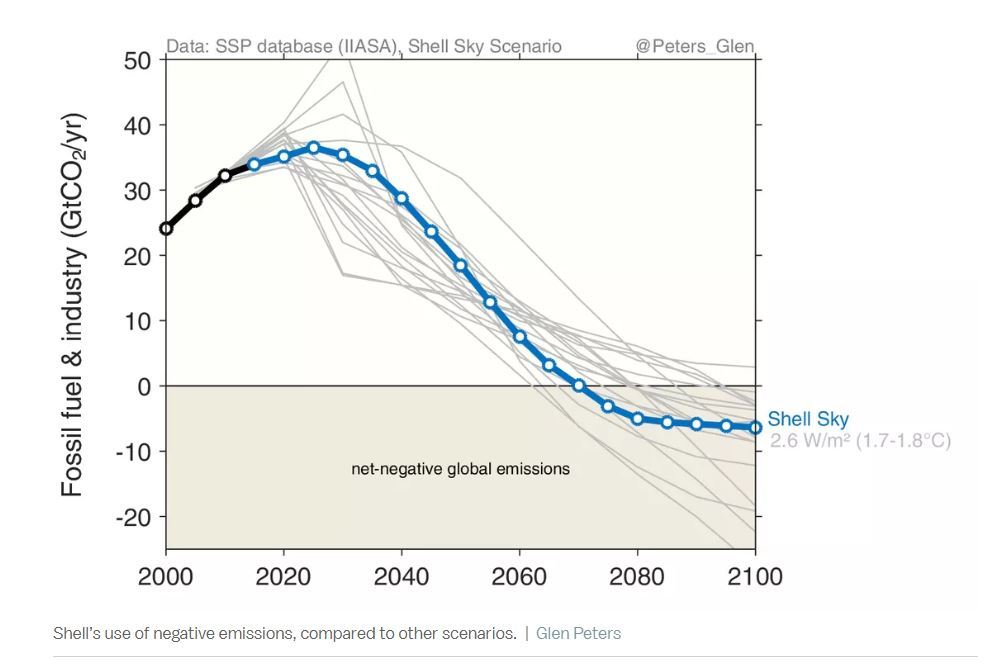

While there is nothing like a real-world plan in place for hitting those targets yet, climate modelers have come up with many scenarios for how we might do so. However, as I wrote recently, most of those scenarios rely heavily on negative emissions — ways of pulling carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere. If negative emissions technologies can be scaled up later in the century, the reasoning goes, it gives us room to emit more earlier in the century.

And that’s what most current 2- or 1.5-degree scenarios show: Global carbon emissions rise in the short term, then plunge rapidly to become net negative around 2060, with gigatons of carbon subsequently captured and buried over the remainder of the century. The oil giant Shell released a scenario along those lines a few weeks ago.

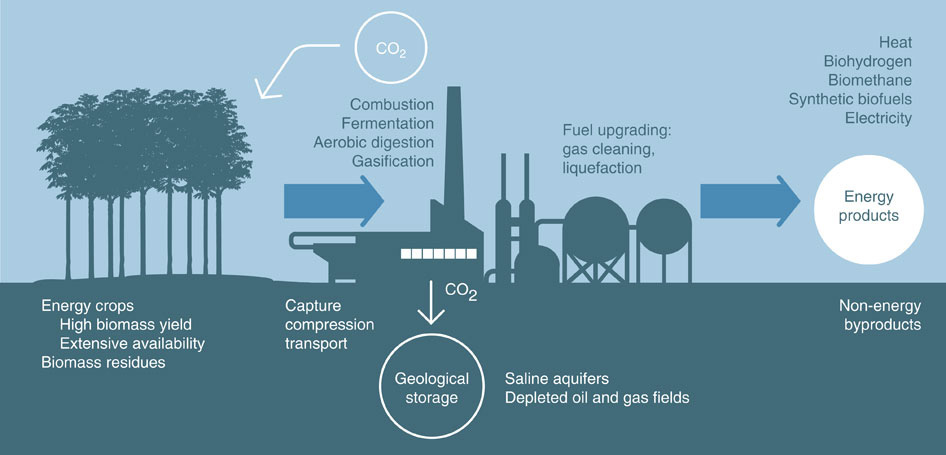

The primary instrument of negative emissions is expected to be BECCS: bioenergy (burning plants to generate electricity) with carbon capture and sequestration. The idea is that plants absorb carbon as they grow; when we burn them, we can capture and bury that carbon. The result is electricity generated as carbon is removed from the cycle — netnegative carbon electricity.

Most current scenarios bank on a lot of BECCS later in the century to make up for the carbon sins of the near past and near future.

One small complication in all this: There is currently no commercial BECCS industry. Neither the BE nor the CCS part has been demonstrated at any serious scale, much less at the scale necessary. (The land area needed to grow all that biomass for BECCS in these models is estimated to be around one to three times the size of India.)

Maybe we could pull off a massive BECCS industry quickly. But banking on negative emissions later in the century is, at the very least, an enormous, fateful gamble. It bets the lives and welfare of millions of future people on an industry that, for all intents and purposes, doesn’t yet exist.

Plenty of people reasonably conclude that’s a bad idea, but alternatives have been difficult to come by. There hasn’t been much scenario-building around truly ambitious goals: to zero out carbon as fast as possible, to hold temperature rise as close to 1.5 degrees as possible, and, most significantly, to do so while minimizing the need for negative emissions. That is the upper end of what’s possible.

In May, I looked at three publications that help fill that gap:

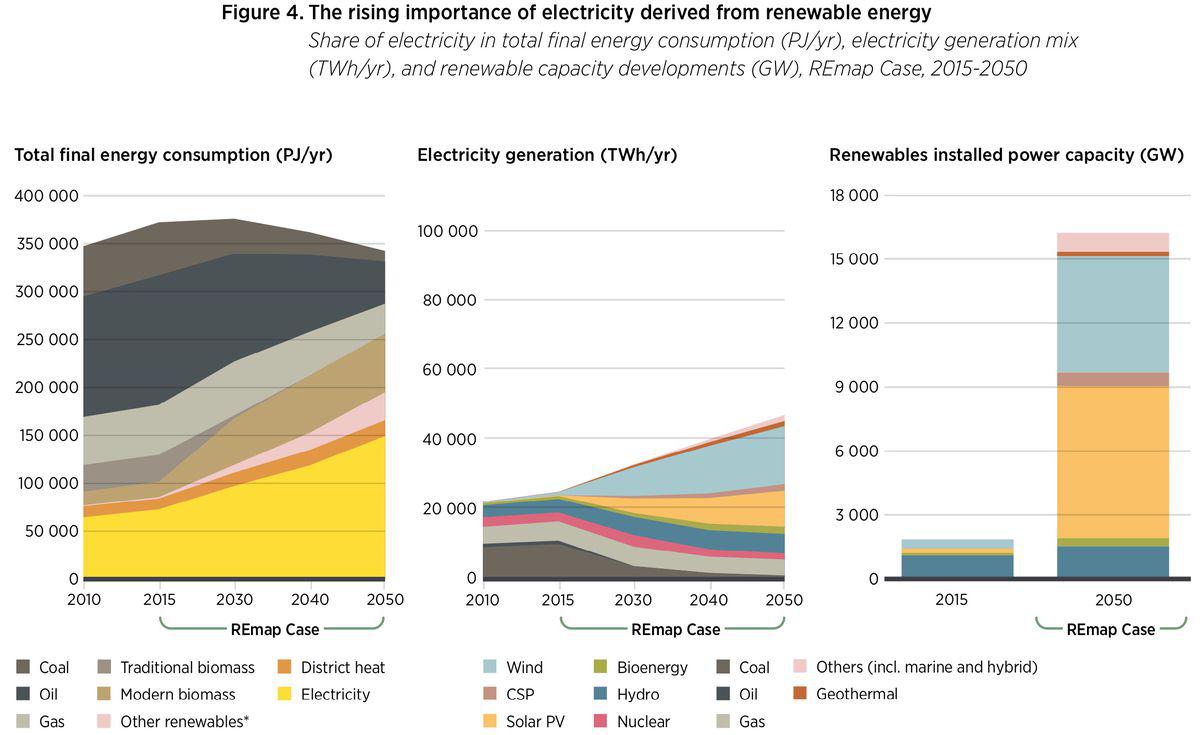

• “Global Energy Transformation: A Roadmap to 2050,” by the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), is a plan that targets a 66 percent chance of staying below 2 degrees, primarily through renewable energy.

• The analysts at Ecofys recently released a scenario for zeroing out global emissions by 2050, thus limiting temperature to 1.5 degrees and eliminating (most of) the need for negative emissions.

• A group of scholars led by Detlef van Vuuren of the Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency published a paper in Nature Climate Change investigating how to hit the 1.5 degree target while minimizing the need for negative emissions.

This graph will be very meaningful once you read the paper.

Here’s how this post (first published in May) is going to go: First, we’ll have a quick look at why targeting 1.5 degrees is so urgent; second, we’ll look at a few things these scenarios have in common, the baseline for serious ambition; third, we’ll look more closely at the third paper, as it offers some interesting alternatives (like, oh, mass vegetarianism) to typical carbon thinking; and finally, I’ll conclude.

Why targeting 1.5 degrees is urgent

Americans can’t make much sense out of Celsius temperatures, and half a degree of temperature doesn’t sound like much regardless. But the difference between 1.5 and 2 degrees of global warming is a very big deal. (Read the IPCC’s new science review here.)

Another recent paper in Nature Climate Change makes the point vividly: Bumping ambition up from 2 to 1.5 degrees would prevent 150 million premature deaths through 2100, 90 million through reduced exposure to particulates, 60 million due to reduced ozone.

“More than a million premature deaths would be prevented in many metropolitan areas in Asia and Africa,” the researchers write, “and [more than] 200,000 in individual urban areas on every inhabited continent except Australia.”

That’s not nothing! And of course, the difference between 1.5 and 2 degrees could mean the difference between life and death for low-lying islands.

There’s no time to waste. In fact, there may be, uh, negative time. Limiting temperature rise to 1.5 degrees is possible, even in theory, only if the “carbon budget” for that target is at the high end of current estimates.

Again: 1.5 is only possible if we get started, with boosters on, immediately, and we get lucky. Time is not running out — it’s out.

What’s required to limit temperature rise to 1.5 degrees

The three scenarios I mentioned are different in a number of ways. The first two project through 2050, but the Nature Climate Change paper goes out to 2100. They target different things and use different tools. But they share a few big action items — features that any ambitious climate plan will inevitably involve.

1) Radically increase energy efficiency

Just how much energy will be needed through 2050? That depends on population and economic growth, obviously, but it also depends on the energy intensity of the world’s economies — how much primary energy they require to produce a unit of GDP.

Increasing energy efficiency (which, all else being equal, reduces emissions) is in a race with population and economic growth (which, all else being equal, increases them). To radically decarbonize with minimal negative emissions, efficiency will need to outrun growth. (Notably, Shell’s scenario shows much higher global energy demand in coming decades; growth outruns efficiency.)

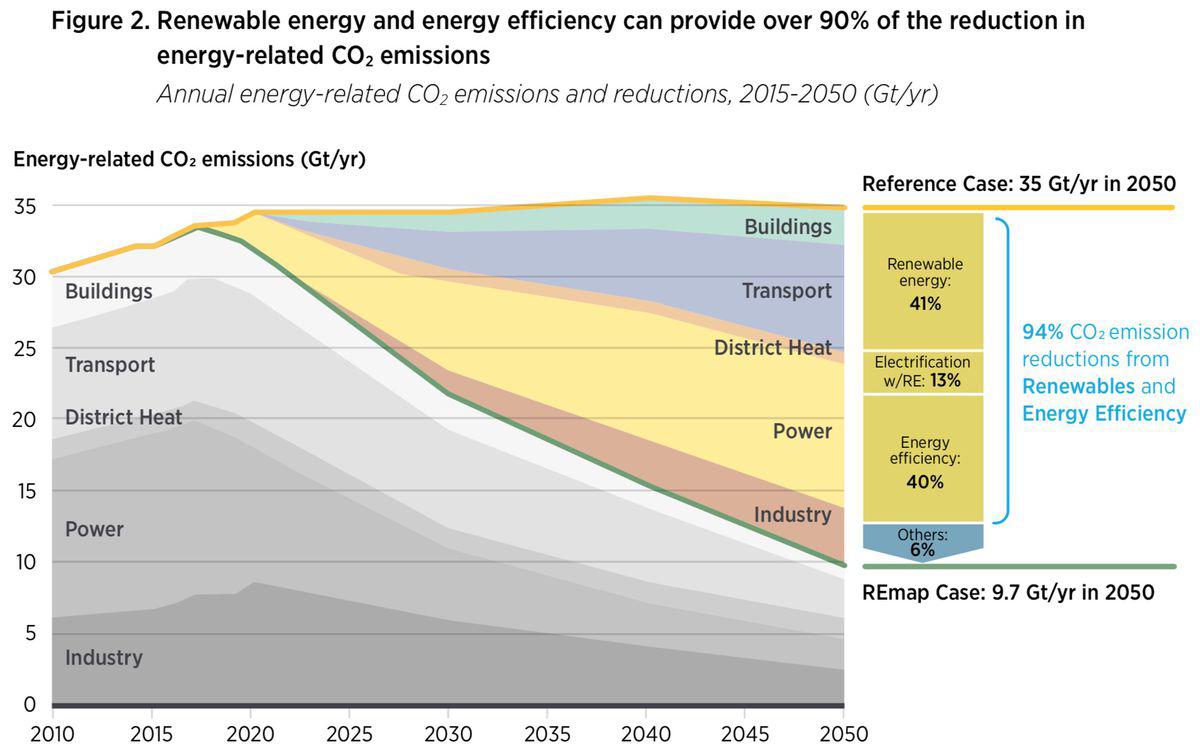

IRENA’s scenario reduces global energy-related emissions 90 percent by 2050. Of that 90 percent, 40 comes from energy efficiency.

To do this, IRENA says, the energy intensity of the global economy must fall two-thirds by 2050. Improvements in energy intensity will have to accelerate from an average of 1.8 percent a year from 2010 to 2015 to an average of 2.8 percent a year through 2050.

In the Ecofys scenario, energy efficiency is so amped up that total global energy demand is lower in 2050 than today, despite a much larger population and a global economy three times larger than today’s.

The Nature Climate Change paper summarizes the necessary approach to efficiency this way: “Rapid application of the best available technologies for energy and material efficiency in all relevant sectors in all regions.”

“All relevant sectors in all regions” means electricity, transportation, buildings, and industry, all bumped up to the most efficient available materials and technologies, everywhere in the world, starting immediately. Cool, cool, cool.

2) Radically increase renewable energy

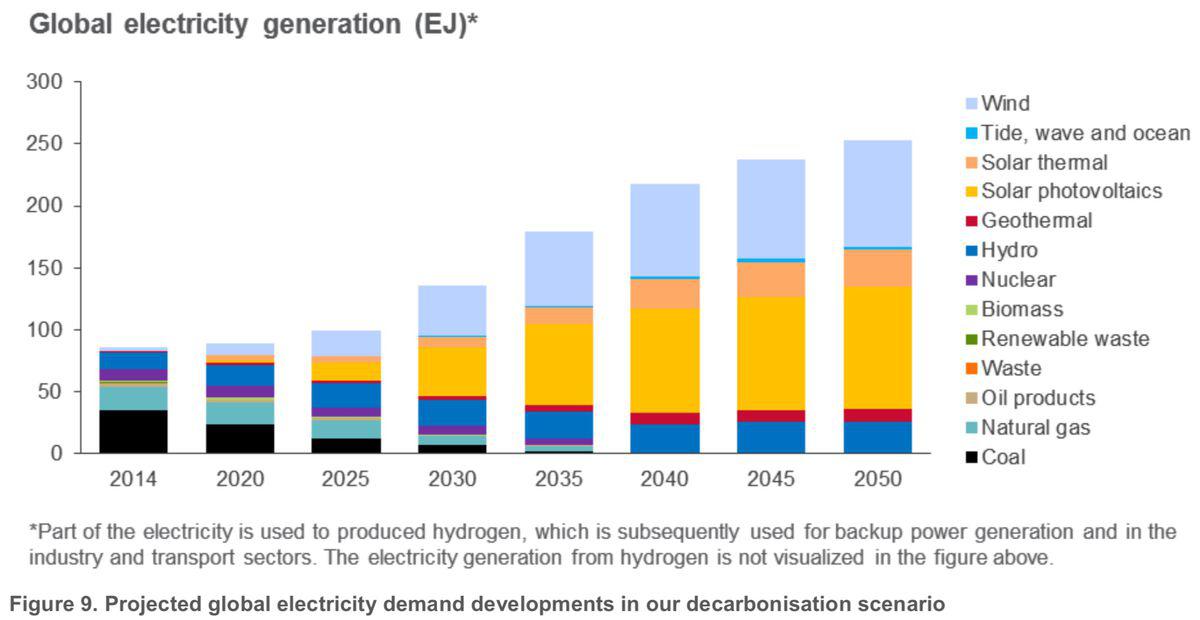

All the scenarios envision renewables (primarily wind and solar) rapidly coming to dominate electricity. In the IRENA scenario, renewables grow six-fold faster than they are currently, supplying 85 percent of global electricity by 2050.

Ecofys has them supplying 100 percent of global electricity — with that sector completely decarbonized — by 2040, even as global demand for electricity triples.

The Nature Climate Change paper notes that the vision of rapid renewables dominance all these scenarios have in common involves “optimistic assumptions on the integration of variable renewables and on costs of transmission, distribution and storage,” which, yeah.

3) Electrify everything!

Notably, all three scenarios heavily involve electrification of sectors and applications that currently run on fossil fuels. In the IRENA case, electricity rises from 21 percent of total global energy consumption today to 40 percent by 2050.

In the Ecofys scenario, it rises to a whopping 70 percent. In the Nature Climate Change study, it rises to 46 percent (compared to 31 percent in the reference case).

I have made the case for electrification before, and it’s not complicated. We know how to radically increase the supply of zero-carbon electricity; increasing the supply of zero-carbon liquid fuels is much more difficult. So it makes sense to move as much energy use as possible over to electricity, particularly vehicles, home heating and cooling, and lower-temperature industrial applications.

The Ecofys scenario makes it particularly clear: If renewable energy and energy efficiency are to be your primary decarbonization tools (more on that in a second), full decarbonization requires going all out on electrification.

The rising yellow wedge at the bottom left — that’s electricity. IRENA

4) And still maybe do a little negative emissions

Even though the intentions, of the Ecofys and Nature researchers particularly, was to minimize the need for negative emissions, neither was able to completely eliminate it.

“Regardless of the rapid decarbonisation” in the scenario, Ecofys researchers write, “the 1.5°C carbon budget is most likely still exceeded.” The only way to hold at 1.5 is to mop up that excess carbon with negative emissions. Ecofys thinks CCS applications will mostly be confined to industry and the rest can be taken care of by “afforestation, reforestation, and soil carbon sequestration,” i.e., non-CCS methods of negative emissions. And, it notes, this remaining excess carbon “is significantly less than most other low carbon scenarios.”

In the Nature Climate Change study, the need for BECCS can be completely eliminated only if every single one of the other strategies is maximized (see the next section).

Here’s what those researchers conclude about negative emissions:

While this study shows that alternative options can greatly reduce the volume of CDR [carbon dioxide removal] to achieve the 1.5°C goal, nearly all scenarios still rely on BECCS and/or reforestation (even the hypothetical combination of all alternative options still captured 400 GtCO2 by reforestation). Therefore, investment in the development of CDR options remains an important strategy if the international community intends to implement the Paris target. They advise policymakers (wisely, it seems to me) to pursue negative emissions strategies but to think of alternative scenarios as insurance against the possibility that those strategies run up against unanticipated social or economic barriers.

Decarbonization beyond renewable electricity and efficiency

The IRENA and Ecofys scenarios, like most rapid decarbonization scenarios, rely overwhelmingly on renewable energy and energy efficiency. But as environmentalist Paul Hawken reminds us with his Drawdown Project, there are more things in heaven and earth than are dreamt of in most climate policy. (For instance, we’re going to talk about fake meat here in a minute.)

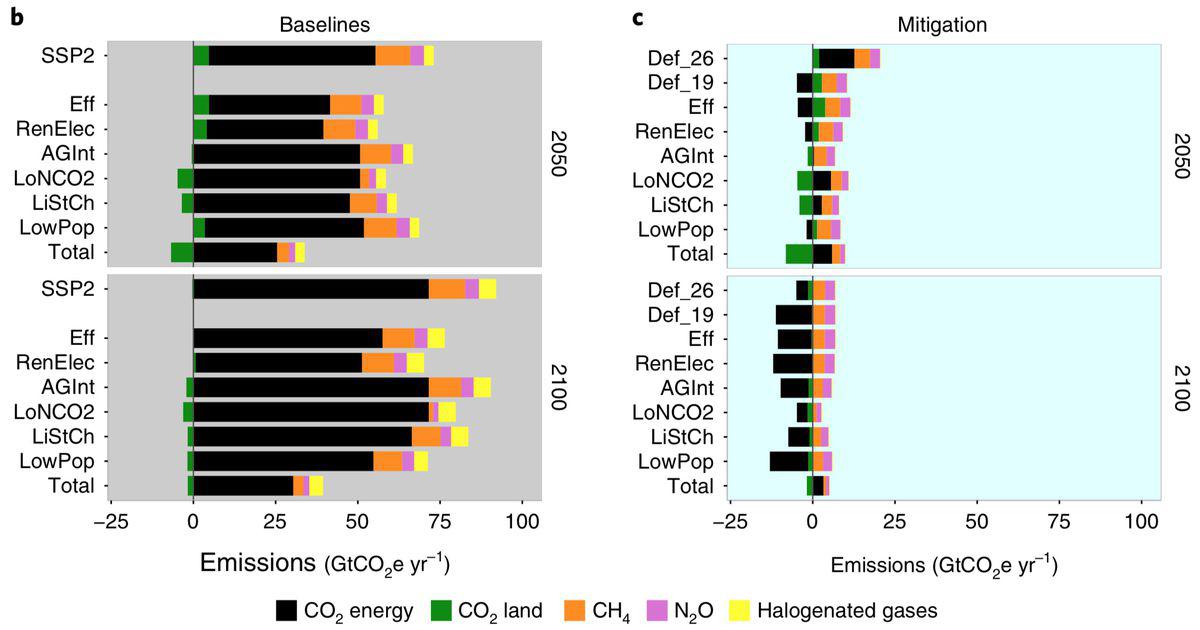

Like most climate-economic modelers, the Nature Climate Change researchers use integrated assessment models (IAMs) to generate their scenarios. They tested their decarbonization strategies against the second of five shared socioeconomic pathways (SSPs), which are the modeling community’s set of different visions for the future — different mixes of population, economic growth, oil prices, technology development, etc. SSP2 contains roughly median predictions. (If you’re curious about SSPs, here’s an explainer.)

But they also challenge some of the limitations in how IAMs have typically been used:

As IAMs select technologies on the basis of relative costs, they normally concentrate on reduction measures for which reasonable estimates of future performance and costs can be made. This implies that some possible response strategies receive less attention, as their future performance is more speculative or their introduction would be based on drivers other than cost, such as lifestyle change or more rapid electrification. The Nature Climate Change paper attempts to model some of these more ambitious, uncertain, or non-costdriven strategies, assembling a whole suite of decarbonization scenarios in different combinations.

Several of them are familiar: There’s a “uniform carbon tax in all regions and sectors,” along with maximized energy efficiency and renewable energy. But others are more novel in these modeling contexts.

Agricultural intensification: “High agricultural yields and application of intensified animal husbandry globally.”

Low non-CO2:“Implementation of the best available technologies for reducing non-CO2 emissions and full adoption of cultured meat in 2050.” (Non-CO2 greenhouse gases include methane, nitrous oxide, black carbon, fluorocarbons, aerosols, and tropospheric ozone. Cattle are a big source of methane, thus the cultured meat.)

Low population: “Scenario based on SSP1, projecting low population growth.” Population growth can be curbed most effectively through access to family planning and education of girls (which, notably, have many other benefits as well).

You can decide for yourself how likely you find any of these changes. The researchers say they are modeling “ambitious, but not unrealistic implementation.”

Reducing non-CO2 GHGs and widespread lifestyle changes have the most short-term impact on emissions. However, “by 2100,” they write, “the strongest reductions are found in the renewable electrification and low population scenarios.” This echoes what the Drawdown Project found, which is that educating girls and making family planning widely available (thus reducing population growth) is the most potent long-term climate policy.

Deep thoughts

Needless to say, accomplishing any one of these goals — a global carbon tax, maximized efficiency, an explosion of renewable energy, a wholesale revolution in agriculture, rapid reduction of non-CO2 GHGs, a rapid shift in global lifestyle choices, and successful measures to curb population growth — would be an enormous achievement.

To completely avoid BECCS while still hitting the 1.5 degree target, we would have to accomplish all of them.

That is highly unlikely. Still, the important point of the Nature Climate Change research remains: “alternative pathways exist allowing for more moderate use and postponement of BECCS.” Given the substantial and uncharted difficulties facing BECCS, policymakers owe those alternative pathways a look.

Obviously these strategies face all kinds of social and economic barriers. (I’m trying to envision what it would take to rapidly shift Americans from beef to cultured meat ... trying and failing.) But they also come with cobenefits. Reducing fossil fuels reduces local air pollution and its health impacts. Energy efficiency reduces energy bills. Eating less meat and driving less are healthy.

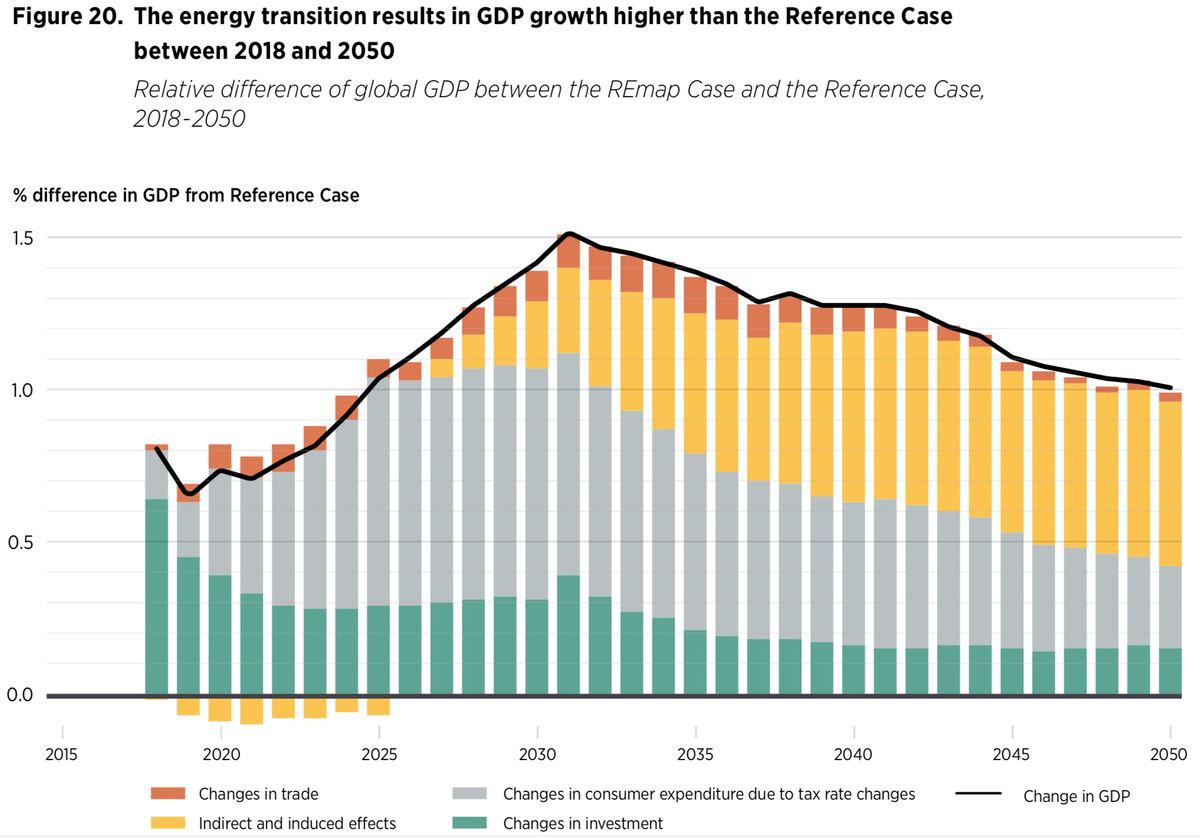

Overall, a radical energy transition would mean a net boost in global GDP (relative to the reference case) in every year through 2050.

An energy transition would also create millions of net jobs. But that doesn’t mean it will be easy.

Engineering any of these shifts, the Nature Climate Change researchers write with some understatement, “requires not only insights from IAMs, but also in-depth knowledge of social transitions.” They suggest (and I heartily endorse) that subsequent research focus on social and political barriers and strategies.

In the end, perhaps the most important conclusion in the Nature Climate Change paper is the simplest and the one that we already knew: “a rapid transformation in energy consumption and land use is needed in all scenarios.”

At this point, whether it’s possible to hit various targets is almost beside the point. All the science and modeling are saying the same thing, which is that humanity faces serious danger and needs to reduce carbon emissions to zero as quickly as possible.

The chances of us getting our collective [act] together and accomplishing what these scenarios describe are ... slim. There are so many vested interests and so much public aversion to rapid change, so many governments to be coordinated, so many economic and technology trends that must fall just the right way. It’s daunting.

Conversely, the chances of us overdoing it — trying too hard, spending too much money, reducing emissions too much or too fast — are effectively nil.

So the only rule of climate policy that really matters is: go as hard and fast as possible, forever and ever, amen.

Updated 28 October 2018

|