Newsletter of the

INTERNATIONAL ENVIRONMENT FORUM

Volume 19, Number 4 --- 15 April 2017

Website: iefworld.org

Article submission: newsletter@iefworld.org

Deadline next issue 13 May 2017

Secretariat Email: ief@iefworld.org General Secretary Emily Firth

Postal address: 12B Chemin de Maisonneuve, CH-1219 Chatelaine, Geneva, Switzerland

Download the pdf version

From the Editor, Request for information for upcoming newsletters

This newsletter is an opportunity for IEF members to share their experiences, activities, and initiatives that are taking place at the community level on environment, climate change and sustainability. All members are welcome to contribute information about related activities, upcoming conferences, news from like-minded organizations, recommended websites, book reviews, etc. Please send information to newsletter@iefworld.org.

Please share the Leaves newsletter and IEF membership information with family, friends and associates, and encourage interested persons to consider becoming a member of the IEF.

IEF Governing Board Elected

The 21st IEF Annual General Assembly in the Netherlands on 15 April (https://iefworld.org/genass21) elected the IEF Governing Board for 2017-2018. The members elected are Arthur Dahl, Laurent Mesbah, Emily Firth, Ian Hamilton, Victoria Thoresen, Wendi Momen, and Sylvia Karlsson-Vinkhuyzen.

There is one change from last year, as Duncan Hanks of Canada was not reelected after many years of loyal service to IEF. He was replaced by Laurent Amine Mesbah of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Laurent was born and grew up in France in a multicultural background, and did research and teaching in plant genetics at the Free University in Amsterdam, the Netherlands, where he completed his PhD. In addition he completed a certificate of advanced studies in Environmental Diplomacy at the University of Geneva and is a founding member of the IEF. Laurent has been living in Bosnia and Herzegovina since 2000 with his family. He has been involved in education and youth empowerment as well as in managing, implementing and evaluating projects related to sustainable development with international organisations. Laurent teaches environmental sciences and value based leadership at the university and co-founded and leads Bloom Earth School in Sarajevo.

IEF at University of Geneva Sustainability Week

The International Environment Forum was invited to participate in Sustainability Week organized by students at the University of Geneva, Switzerland. One theme was the role of international organizations in implementing the Sustainable Development Goals, and IEF had a stand explaining its activities, including its last conference in Bolivia on implementing the SDGs at the community and individual levels.

IEF International Conference, de Poort, The Netherlands, 14-17 April 2017

The 21st International Environment Forum Conference was held in partnership with the Justice Conference in de Poort, the Netherlands, on 14-17 April 2017. The theme of the Justice Conference was "From Disintegration to Integration: navigating the forces of our time". This report is not comprehensive, but only features the International Environment Forum events and a few other highlights.

Justice Conference group photo

Friday, 14 April

The opening plenary included the screening of materials from the Quiet Genocide project, documenting the decades-long persecution of the Baha'i community in Iran.

.

.

de Poort Conference Centre; the audience

In the evening, the IEF organized the following workshop:

"Environmental Changes as forces for disintegration and integration"

IEF panel: Laurent Mesbah, Sylvia Karlsson-Vinkhuyzen, Joachim Monkelbaan, Arthur Dahl

Human pressures are causing extreme climate change and the sixth mass extinction, among other environmental catastrophes. These manifestations of disintegration in ecosystems and the entire earth system require compensating efforts of integration including global environmental governance. Nature demonstrates the complementarity of disintegration and integration. Similar processes operate in human society, and systems science helps to explain their relationship. Higher levels of human integration may depend on ethical values including from religion. Climate change provides an example of the need for innovation in integrating different societal dimensions such as science, education and governance. This workshops will explore a set of topics linked to this theme through presentations and interactive discussions.

The first presentation was on Environmental Changes as forces for disintegration and integration by Prof. Laurent Mesbah of the American University in Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina. He showed how nature offers beautiful examples of disintegration and integration as organic processes, at the molecular, cellular, organism, species, population, community, and ecosystem level. All living processes are essentially organic and follow precise and beautifully regulated natural laws, such as seasonal cycles. Spring is a physical rebirth of organic matter and life, as well as a symbol of renewal or rebirth used in many cultures and old traditions maintained througout the ages.

The son of the founder of the Baha'i Faith, a great thinker and wise man 'Abdu'l-Bahá, wrote: "Reflect upon the inner realities of the universe, the secret wisdoms involved, the enigmas, the inter-relationships, the rules that govern all. For every part of the universe is connected with every other part by ties that are very powerful and admit of no imbalance, nor any slackening whatever“.

If we look at the forest ecosystem for example we can see a disintegration of dying living organisms and materials such as leaves in the fall from which decomposers feed. Decomposers such as insects, fungi and bacteria actually thrive on this abundant source of energy, and provide nutrients from which green plants will benefit, build material and store energy captured from the sun. Decomposers such as insects in turn become a source of food, for example, for forest insectivore birds who in turn can also become a prey for other predators, connecting other organisms through the food chain and food web in the forest ecosystem. In this and all other ecosystems integration and disintegration are therefore very tightly connected and interdependent.

What can we say about human societies and these forces of integration and disintegration? We do have significant evidence of important negative impacts on the natural environment. The impacts of humans on planet earth have become so profound that scientists call this time the Anthropocene era. The disintegrating processes which include climate disruption, biodiversity loss, habitat destruction and unsustainable use of natural resources constitute a real crisis and threat for humanity and for many forms of life. Human societies themselves are facing many crisis such as inequalities, financial, social, and all kind of injustices today are adding to each other and seem to be interconnected. Perhaps if we look at the root causes of these crises we could understand how these disintegrating forces can provide the driving forces needed to build more just and sustainable human societies in better harmony with their natural environment.

DOWNLOAD PRESENTATION 1.2MB

.

.

Laurent Mesbah (left); Arthur Dahl

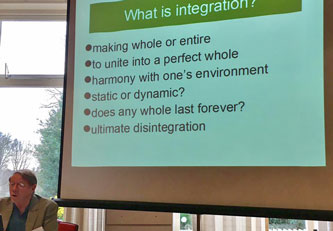

In the second presentation on The Systems Science of Disintegration and Integration, Dr. Arthur Lyon Dahl of Geneva, Switzerland, asked what is integration? It is making whole or entire, to unite into a perfect whole, or harmony with one’s environment. But is it static or dynamic? Does any whole last forever? Ultimately everything disintegrates. There are cycles of integration and disintegration. Stars are born and die, our body grows and deteriorates, religions are born and decline, civilizations rise and fall.

What are the qualities of a young integrating system versus an old disintegrating one? Flexibility versus rigidity, innovation versus resistance to change, diversification versus rejecting differences. In a highly integrated system like a coral reef, we see cooperation, symbiosis and complementarity; inclusiveness; efficiency of exchanges, communications and networking; increasing capital stock, economy in resource use, efficient cycling, little waste; high energy capture and effective use of its flow through system; and high diversity and specialization of functions.

What causes disintegration? There are internal causes like imbalances escaping from homeostatic mechanisms, failures in resilience, rigidity and overspecialization, inadequate diversity leading to instability, and accumulation of disfunctions with age. There are also external causes such as changing environmental conditions beyond the limits a system is adapted to, sudden shocks or damaging events, competition from a more dominant system, and conditions creating new potentials for which the system is not well adapted.

Peter Turchin (Nature 7281:608, 4 February 2010, doi:10.1038/463608a) has modeled the rise and decline of civilizations mathematically, using social cohesion versus collective violence as an indicator. He found that population growth and new technology generate wealth for the elite, until an oversupply of labour increases poverty and allows the concentration of wealth, resulting finally in factionalism, anarchy and collapse on about a 200 year cycle. He predicted political instability and impending crises in Western Europe and the USA peaking in 2020, and highlighted the need to reduce social inequality.

Complex systems do not usually follow a smooth evolutionary curve towards greater integration and complexity, but experience what is called a punctuated equilibrium, with periods of stability interrupted by times of rapid change with bursts of creativity and reorganization. Dominant entities like the dinosaurs that have over-specialized and have lost the capacity to adapt die out, to be replaced by entities capable of rapid change and with new potentials for increased efficiency and integration (think early mammals). Human social systems seem to follow a similar pattern, and recent research suggests that higher levels of human organization can only be explained by the ethical principles of religion (Turchin, Ultrasociety, 2016). New values are the catalyst for a new cycle of integration. The present time, with accelerating disintegration of the old system and embryonic development of the new more integrated system of a planetary civilization, would call for learning communities accustomed to a culture of change and founded on strong spiritual principles.

DOWNLOAD PRESENTATION 222KB

Dr. Joachim Monkelbaan of the Transitions Hub of Climate KIC in Brussels, Belgium, followed with a presentation on Systems innovation for climate change. He started by reviewing the forces for disintegration and integration.

The first force, technology, has brought us closer together, but also has led to cybercrime, new weapons, smartphone over-use, social media polarizing through confirmation bias, dissemination of ‘fake’ news, and destruction of jobs.

The second force is globalization, the international integration arising from the interchange of world views, products, ideas, and other aspects of culture. But most jobs are lost to productivity increases rather than trade and delocalization. We worship growth, but it has only benefited the workers in China and the very rich, not the very poor or the middle class.

The third force is climate change, which the US military and intelligence consider a threat to national security. The transitions necessary to respond to rising population, affluence and climate change require systems innovation. Complex systemic problems require envisioning the future or backcasting; learning, reflexivity and adaptiveness; systems thinking to address complexity and realize transformational change at scale; participation involving stakeholders to affect the way systems work; and serendipity to leverage crisis for purposive or compulsory decision-making.

Innovation is usually perceived as technical rather than about social change but the systems perspective obviously shifts that perspective. Integration is important at the science-policy-practice interface and in education. Bahá'í principles can shed new light on these issues.

Since humans are fundamentally spiritual beings and are multi-dimensional, we need an understanding of behavioural, psychological, and spiritual aspects, and a revolution in awareness to modify the human behaviour that drives climate change.

Bahá’ís are encouraged to see in the revolutionary changes taking place in every sphere of life the interaction of two fundamental processes. One is destructive in nature, while the other is integrative; both serve to carry humanity, each in its own way, along the path leading towards its full maturity (Universal House of Justice, To the Bahá’ís of Iran, 2 March 2013). This is nothing new. In Taoism, the interaction between Yin and Yang, between integration and disintegration, is taken to produce and change the universe, to create being and non-being.

DOWNLOAD PRESENTATION 3.3MB

.

.

Joachim Monkelbaan; Sylvia Karlsson-Vinkhuyzen

In the final presentation on The promises and pitfalls of integration in governance, Asst. Prof. Sylvia Karlsson-Vinkhuyzen from Wageningen University, the Netherlands, showed how integration emerges frequently in current discourses on governance. The increasing functional interdependencies between traditionally separate policy areas such as energy, agriculture, health etc. leads to calls for integration in policy and implementation. Concepts such as environmental policy integration and mainstreaming of the environment appear in development plans and policy papers of national and international organizations. The Sustainable Development Goals and the Agenda 2030 in which they are embedded are explicitly 'integrative’ and ‘indivisible’ among its 17 goals and 169 targets, many of which are synergistic while some are clearly antagonistic.

She started by discussing problems in international governance such as mainstreaming fatigue, prioritization conflict, trade-offs, and accountability constraints. She then cited promising principles such as becoming protagonists of our own development: “care must be taken lest people be treated primarily as passive objects to be developed, rather than as protagonists of development in and of themselves” (Baha’i International Community, Summoning our Common Future, 2015).

The most important principle is that “the purpose of Justice is the appearance of unity among men” (Bahá'u'lláh). It is essential to redefine fundamental goals: “...it is clear that the honour and exaltation of man must be something more than material riches. Material comforts are only a branch, but the root...is the good attributes and virtues which are the adornments of his reality...” ('Abdu’l-Bahá), and to internalize responsibility: ...the love and knowledge of God, universal wisdom, intellectual perception, scientific discoveries, justice, equity, truthfulness, benevolence, natural courage and innate fortitude, the respect for rights and the keeping of agreements and covenants; rectitude in all circumstances, serving the truth under all conditions, the sacrifice of one’s life for the good of all people; kindness and esteem for all nations...” ('Abdu’l-Bahá).

DOWNLOAD PRESENTATION 1.9MB

The workshop concluded with a general discussion on the main theme.

Saturday 15 April

In the Saturday morning plenary, Vincent Cillessen of the War Crimes Unit of the Dutch Police provided perspectives from a National War Crimes Unit: Tools to Fight Impunity for Syrian War Crimes outside of the International Criminal Court or an Ad Hoc Syria Tribunal. He described the activities possible at the national level to document war crimes in an ongoing conflict with the aim of the eventual prosecution of war criminals.

Four parallel workshops followed. In one, Prof. Graham Hassall from Victoria University in Wellington, New Zealand, spoke by video link on "Justice and Global Governance: A view from Oceania".

.

.

workshops

The afternoon plenary featured Simin Fahandej from the Baha'i International Community in Geneva, and Drs. Marjolijn Snippe, For a Friendly Planet, speaking on "Governance by International Institutions and Global Democracy through the United Nations". Parallel workshops continued in the afternoon.

.

.

Marjolijn Snippe and Simin Fahandej; workshop

The IEF Annual General Assembly was held on Saturday evening 15 April 2017 at de Poort, with the presentation of the annual report, election of the Governing Board, and consultation on future activities. [see separate report]

Sunday 16 April

The Sunday morning plenary by journalist and journalism professor Corinne Podger speaking by video from Melbourne, Australia, was on "The Mirror of the World: Perspective on the Modern Media Environment" in which she discussed the impact of Internet media on responsible journalism. She highlighted the challenges of finding trustworthy sources of news, when there were commercial interests in supporting confirmation bias, false news, and alternative truth. She also underlined the risks to professional journalism as advertizing revenue moved from newspapers and news broadcasters to free social media and people were no longer willing to pay for reliable news.

In a second plenary on "Two Billion Eyes: Bringing Vision to Millions of People Requires Everybody's Participation", Kathleen Holmlund and Bijan Aazami described the latter's efforts to provide cheap glasses to the one billion people who cannot access education or participate fully in society because of poor eyesight. This was followed by a sharing of personal stories about the justice challenge.

opportunities for exchanges over meals and during breaks

The afternoon plenary was on the "The Women's Movement and Use of International Legal Instruments" by Zarin Hainsworth of the United Kingdom, followed by further parallel workshops. The final plenary of the day was by Dr. Moojan Momen (U.K.) on "Islam and the West", tracing the rise and fall of a rational, tolerant Islamic civilization and the eventual transfer of science and reason to an emerging more secular West.

The evening featured a projection of excerpts from Yann Arthus Bertrand's film "Human" followed by a discussion led by Carmel Irandoust on the reactions it produced and their ethical implications.

Monday 17 April

The final morning of the conference featured a second brilliant plenary talk by Moojan Momen on "Power and the Baha'i Community", contrasting the problems that have resulted from the hierarchy, hegemony and patriarchy of the present system in which power is maintained by competition, wealth accumulation and force, and the Baha'i approach in which there is no contention for power, power is with institutions rather than individuals, decisions are made through consultation, and the system is built through a practical path with programmed action and participation in a culture of learning.

.

.

Moojan Momen

After a final set of parallel workshops, conference organizer Maja Groff (The Netherlands) reviewed conclusions and outcomes from the Justice Conference for building integrated communities.

.

.

Maja Groff; Maja Groff and IEF board member Wendi Momen

ABOUT THE IEF PANELISTS

Laurent Amine Mesbah

Born and grew up in France in a multicultural background, Laurent Mesbah did research and teaching in plant genetics at the Free University in Amsterdam, the Netherlands, where he completed his PhD. In addition Dr Laurent Mesbah completed a certificate of advanced studies in Environmental Diplomacy at the University of Geneva and is member of the International Environment Forum since its foundation. Laurent has been living in Bosnia and Herzegovina since 2000 with his family. He has been involved in education and youth empowerment as well as in managing, implementing and evaluating projects related to sustainable development with international organisations. Laurent teaches environmental sciences and value based leadership at the university and co-founded and leads Bloom Earth School in Sarajevo.

Arthur Dahl

Dr. Arthur Lyon Dahl is President of the International Environment Forum and a board member of ebbf - Ethical Business Building the Future. A scientist by training, he has 50 years' experience on sustainability, international environmental governance, development, indicators, and systems science. A retired Deputy Assistant Executive Director of UNEP, he lived and worked many years in Africa and the Pacific Islands, and consults with the World Bank and UNEP. His recent work includes values-based education for sustainability. His books include: "Unless and Until: A Baha'i Focus on the Environment" and "The Eco Principle: Ecology and Economics in Symbiosis".

Joachim Monkelbaan

Joachim Monkelbaan, has recently been named manager of the Transitions Hub of Climate KIC in Brussels, Belgium. He has degrees in law and recently completed a Ph.D. at the University of Geneva looking at international governance for the transition to sustainability. He previously worked for IUCN, UNEP and the International Centre for Trade and Sustainable Development.

Sylvia Karlsson-Vinkhuyzen

Sylvia works as Assistant Professor with the Public Administration and Policy Group of Wageningen University since 2011 and is also Adjunct Professor in Global Environmental Governance with the University of Helsinki, Finland. Sylvia’s in her research seeks to understand the key determinants of what makes global governance processes with environmental and social implications exert influence and build legitimacy where issues such as transparency, participation, accountability and equity are important. She has published on the domains of global energy governance, global climate change governance and global sustainable development governance – particularly the evolution and legitimacy of international norms. She is a senior research fellow of the international Earth System Governance Project, a board member of the IEF, CIVICUS and One World Trust.

UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights and the Environment

On March 8, the UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights and the Environment, John Knox, presented his annual report to the Human Rights Council. This year’s report explains that the full enjoyment of human rights depends on biodiversity, and describes how the exercise of human rights is important to the protection of biodiversity. A World Post article on the report is available here. His statement to the Council is available in written form here, and a video of the presentation and the interactive dialogue with governments and other participants is here. On March 24, the Council adopted a resolution on human rights and environment that takes note of the report on biodiversity, and encourages States to adopt an effective normative framework for the enjoyment of a safe, clean, healthy and sustainable environment, including biodiversity and ecosystems.

Report on pesticides. Also on March 8, Hilal Elver, the Special Rapporteur on the right to food, presented a report to the Council that she had prepared with the Special Rapporteur on toxic substances, Baskut Tuncak, on the dangers of pesticides to human health and the environment. Their report describes research showing that pesticides cause an estimated 200,000 acute poisoning deaths every year, the vast majority of which occur in developing countries. The Special Rapporteurs have called on governments to negotiate a new international treaty to regulate and phase out the use of dangerous pesticides.

New website on environmental human rights defenders. On March 6, Universal Rights Group and several other partners, including John Knox, announced the launch of a new web portal with information and links for environmental human rights defenders – that is, those who defend the environment and the human rights that depend on it. As Global Witness has described, environmental defenders are increasingly under threat: at least 185 were killed in 2015 alone. Called www.environment-rights.org, the new site describes the rights of environmental defenders, includes links to sites of international organizations and others who can help them, and provides a great deal of other relevant information. The organizers plan to continue to add to the site in the future, and to translate it into other languages, including Spanish and French.

Online Interfaith Course on Climate Change

The Wilmette Institute is again be offering an 8 week online course on Climate Change starting 15 April 2017. This is the seventh repeat of the course developed by IEF member Christine Muller (Rhode Island, USA), with Arthur Dahl (Geneva, Switzerland) and Laurent Mesbah (Sarajevo, Bosnia-Herzegovina) as supporting faculty.

The course covers the basic science of climate change and provides an understanding of how climate disruption impacts us today and will continue to affect us in the future. Course participants will explore ethical questions related to climate change and address them in the context of the spiritual teachings of the world’s religions, especially those of the Baha’i Faith.

The course helps participants to consider changes in lifestyle and community action for environmental and social responsibility. It shows how to rise above partisan politics and to use both science and religion for the well-being of humankind. There are numerous optional resources for those who want to go more deeply into the issues. People of all religious background are welcome to participate.

For more information and to register, go here:

http://www.cvent.com/events/climate-change/event-summary-5b4d4afa7ca14bb3af3b4043a2319422.aspx

Nature as a Tool to Teach Children Life Skills

by Laurent Mesbah, Bloom Earth School research director and Rebecca Teclemariam Mesbah, academic director at Bloom School

Building on Sarajevo Bloom school vision of an education which integrates intellectual, physical and spiritual development, Bloom Earth School started its activities in June 2016 when the land around the school was prepared and planted. The first harvests came in September the same year with the new school year. Children and youth from every age from preschool to high school have been increasingly taking part in the activities following the seasons. Consciously or not, their connection with nature increases through their senses, their feelings, emotions and their bodies. They feel more relax and more focused to learn as they study. They learned to use garden and construction tools, built the garden shed for the tools. Children observe how weather affects plants; how seeds sprout; how plants grow; how gardeners cope with plant problems; how soil, water and sunshine interact; how butterflies and other insects play a role. Their understanding of nature, its biodiversity, its mechanisms and processes increases.

How does work in nature foster responsibility in young children? It encourages children to use their hands to prepare the soil, sow seeds, remove weeds, water regularly and harvest the crop. When children accept these responsibilities, we help them to become caring individuals. And when children experience the loss of plants because of neglect, they learn the tragedies of improperly caring for the plants. Through these real-life lessons in gardening, children develop an appreciation for the virtue of responsibility.

As winter draws to a close in Sarajevo, and spring shows its first glories, activities in Bloom are increasing outside. Preparations have been well underway already since November 2016 when the greenhouse was built and fruit trees were planted. At the end of January 2017 the first seeds were planted in the nursery with the help of teachers and the children, and many children were involved in planting seeds in the classrooms by preparing their own little recycled pots. Young tomatoes, paprika, zucchini, eggplants and aromatic herbs, and flower seedlings will soon be ready to be planted in the greenhouse and outside. Some students started measuring the temperature in and outside the greenhouse and noticed a significant difference. Lettuce salad is growing and spring onions are getting ready soon. Potatoes, onion, peas, garlic, red beet have been planted with great care. Observing the process of growth and change enables children to anticipate and be patient, rather than expecting immediate gratification. As birds are getting more vocal, primrose flowers and crocuses showing their true color, Bloom Earth School is entering another season of fruitful learning.

More on Bloom School and Bloom Earth School at http://www.bloom.edu.ba/ and http://www.bloom.edu.ba/bloom-earth-school/ and https://www.facebook.com/bloomearthschool/?ref=aymt_homepage_panel

How to Kick the Growth Addiction

Interview with Tim Jackson by Allen White

Great Transition Initiative (April 2017)

http://www.greattransition.org/publication/how-to-kick-the-growth-addic…

The author of Prosperity Without Growth discusses why we need to get past the obsession with economic growth – and the capitalist system that spawns it

Jackson is Professor of Sustainable Development at the University of Surrey and Director of the Centre for the Understanding of Sustainable Prosperity (CUSP). He has been at the forefront of international debate about sustainable development for almost three decades. The second edition of his widely read book, Prosperity Without Growth, was released in 2016.

Endless economic growth, long the rallying cry of the conventional paradigm, endangers our future. Ecological economist Tim Jackson, author of Prosperity Without Growth: Foundations for the Economy of Tomorrow, explores the need to envision a post-growth economy with Allen White, Senior Fellow at the Tellus Institute.

You are widely recognized as a leader in the field of post-growth economics, yet you started your career in in mathematics and philosophy. What drew you to your current focus?

Physics in the mid-1980s in the UK was a difficult and unfulfilling place. I found no joy in the academy, which was not interested in the ideas to which I was drawn. At that time, I also had a passion for playwriting, and the BBC picked up some of my work. After completing my PhD, I moved to London to make a living as a playwright.

It seemed like a good idea, at least until I received my first few paychecks. I was doing odd jobs to supplement my meager income when, in April 1986, the fourth reactor in Chernobyl melted down. That event galvanized my interest in the nexus of economics, technology, and the environment, and inspired me to make a visit to Greenpeace, where I expressed my skepticism of nuclear technologies and my desire to help develop and promote alternatives. I started working as a volunteer and then as a freelancer, analyzing the economics of renewable energy technologies. Before I knew it, without intention or design, I was an ecological economist. The world told me what it wanted me to do. And I haven’t looked back. After thirty years, I still write plays. But the visit to Greenpeace remains pivotal to my trajectory.

Has your playwriting affected your ecological ethos, and vice versa?

Yes, it has, and in interesting ways. In 1999, I wrote a 30-episode series that the BBC marketed as an environmental thriller. It explored the tension between economic development and ecological resilience. I used playwriting partly to give voice to the unspoken dimensions of my internal dialogue. In academia, evidence and rationality are paramount in drawing conclusions and advancing new theses about how the world works. It is a logical but heartless process, leaving no voice for emotion or instinct. Playwriting gave me a wonderful outlet for that.

One of my plays featured a hard-nosed, survival-of-the-fittest advocate of development at all costs. She was probably one of my most vivid characters, and served as my alter ego in an environmental drama informed by my academic training. This and other plays allowed me to use different characters to explore both sides of the economy-ecology nexus as well as issues such as the social psychology of consumption and the tension between altruism and selfishness. My plays and my professional endeavors have been mutually enriching and therapeutic, a marriage of heart and mind.

In your acclaimed book Prosperity Without Growth, you debunk the widely held belief that prosperity and economic growth are inseparable. Why is the conventional wisdom so wrong and so widespread?When the UK Sustainable Development Commission, on which I served, first launched an inquiry into the relationship between prosperity and growth, we pitched it as “redefining prosperity.” I talked about how the potential conflict between a growth-based economy and a finite planet was a timely, indeed essential, issue for the government to address. This, however, was not warmly received. A Treasury official at one of the early meetings responded, “Now I see what sustainability means. It means going back to live in caves. And that’s what you’re all about, isn’t it?”

This exchange, coming early in the inquiry, exposed an almost visceral fear underlying the political response to any questioning of growth. In the course of our deliberations, I learned to accept the legitimacy of such fears. The economy as currently organized relies on growth to produce jobs and ensure financial stability. At the same time, our financial system, coupled with government spending and control of money, collectively serves as a lubricant to help achieve these goals.

The hegemony of the growth-based model often prevents people from questioning its core assumptions. In a very simplistic sense, the conventional wisdom argues that all we have depends on this growth-based system, so why would we want to rock the boat and set ourselves on a path back to cave-dwelling? However, as I argued early in the Commission’s inquiry, we need to openly acknowledge the dilemma in which we are trapped: If endless growth is essential to prosperity and, at the same time, leads to ecological destruction, what should we do? Working with the Commission reminded me of playwriting in some ways, like a drama in which the protagonists were basically saying, “Don’t touch growth; it’s sacrosanct. Keep your dirty mitts off it.” The structural, possibly psychological, maybe even religious affinity for growth impedes our ability to think clearly about our situation. Throughout the inquiry, I sought to open a space—creative, intellectual, and political—to explore this dilemma whereby growth both drives prosperity and erodes the very preconditions for its sustainability. Revealing the contradiction between relentless expansion of income and throughput, on one hand, and ecological survival, on the other, lay at the center of my work.

Do you attribute the growth imperative to the global capitalist system?

Up to a point, yes. Take the example of the UN Sustainable Development Goals, the work of countless individuals and meetings that concluded with the adoption of 17 goals and 169 specific targets. The eighth SDG links “decent work” and “economic growth,” a mirror of the conventional wisdom that dominates political discourse. Of course, the logic is understandable, as is the fear of a post-growth economy. Without growth, the argument goes, job creation will falter, leading to high unemployment and social instability, a recipe for ending the career of any politician.

Still, the durability of the argument is puzzling. The complex relationship between growth and jobs is mediated by labor productivity and technological advances. Nonetheless, politicians are mentally locked into a growth-jobs-prosperity trifecta, a mindset which itself is hostage to the dynamics of modern capitalism.

In order to get beyond this trap, we need to question the fundamental assumptions guiding modern capitalist societies. Addressing the inequalities that capitalism produces, the common argument goes, requires more of the very thing that gives rise to inequality in the first place. Let unbridled growth continue in order to raise all boats. Without it, the poor will not be lifted, and the government will have no money to spend. Capitalism is sacrosanct; it is the best way to achieve growth. This logic resides at the center of learned journals as well as mainstream policy solutions to avoid economic stagnation as measured by conventional metrics. It is a sociological phenomenon as much as an economic one.

You have criticized technological optimists who believe that we can achieve sustainability via deep cuts in emissions and resource use without rethinking economics. Why are such technical solutions insufficient?

I am fascinated by technological optimism, in part because, thirty years ago, I myself was somewhat of a technological optimist. I was looking at the damage of nuclear fission and saying, “Actually, we have better options than that. We have renewable technologies, there are efficiencies that we can create, and we have more resource-productive avenues for technological development. Why not pursue those?”’

For my students, it is a very tempting perspective. In a recent cross-faculty undergraduate course, I paraphrased Ronald Reagan’s response to the classic Limits to Growth: “There are no limits to growth, because there are no limits to human ingenuity and creativity.” The students found this idea of the boundlessness of human creativity very attractive. I showed them a graph depicting the relationship between carbon intensity and economic growth and what it will take to achieve major strides in decarbonization. Their response? “Surely we have the technologies to meet our targets within a few short decades.” Indeed, this response was the same as mine many decades ago. But the difficulty then, as it is now, is that such a dramatic transition, even if economically and technologically plausible, cannot occur in a society in which the entrenched forces of free market capitalism and the inertia of dominant institutions are committed to obstructing the change required.

In my work on the Sustainable Development Commission, I came to realize that the relentless appetite of human beings for consumption coupled with the relentless appetite of capitalists for accumulation, is fueling the planetary emergency. Despite technological progress, the unholy alliance between human nature and institutional structure creates a dangerous lock-in that diminishes prospects for a livable future.

In your book, you identify four pillars of a post-growth economy—enterprise as service, work as participation, investment as commitment, and money as a social good. Explain what you mean by these factors and how they can help us envision a new economy.

These pillars flow in part from the so-called impossibility theorem, which posits that structures in the existing system coupled with certain aspects of human nature make a post-growth world implausible. So we are compelled to ask, where is the solution space? Can we imagine an economy in which enterprise provides outputs that enable people to flourish without destroying ecosystems; where work offers respect, motivation, and fulfillment to all; where investment is prudential in terms of securing long-term prosperity for all humanity; and where systems of borrowing, lending, and creating money are firmly rooted in long-term social value creation rather than in trading and speculation?

Two of those pillars have been present in responses to the environmental crisis for more than two decades, namely enterprise as service and the concept of green or clean investment. In the first case, “servicization” is the idea that the value of materials—chemicals, energy, forests—is not intrinsic to the materials themselves, but rather arises from the services they offer, e.g., cleaning, heating/lighting, and packaging/shelter. Reframing value in this way opens a broad array of pathways toward dematerialization. I was exposed to this concept very early on through the concept of energy services when I was working for the Stockholm Environment Institute and Friends of the Earth. I have always found it profoundly transformational, and the deeper I got into it, the more I realized that you could apply that concept to all sorts of things, including nutrition, health, and housing. I have watched the idea appear in product responsibility legislation, including take-back and product leasing. I use servicization to illustrate how a seemingly intractable lock-in (limitless growth in material throughput to satisfy consumption demands) can be overcome by reimagining fundamental assumptions about the economy and human behavior.

In the case of investment, clean technology is an obvious and urgent example. Here the core concept is that finance capital must be a servant to a higher purpose than maximizing returns on investment. During the financial crisis, when I was writing the original Sustainable Development Commission report, the concept of a Green New Deal emerged. The UK Prime Minister at the time, Gordon Brown, took the idea to Davos with the centerpiece being a massive investment in a low-carbon transition.

These two examples demonstrate ways to overcome seemingly intractable environmental problems associated with a growth-driven economics. They open new possibilities for developing alternative forms of enterprise, based on novel ownership structures and work practices, and for dismantling the notion that money is an end itself instead of a means of exchange for building prosperous societies. And from there, new forms of economic activity can be conceptualized in ways that refashion human activities to operate in harmony, rather than in conflict, with nature.

The building blocks of a new economy are within reach. While current trends may well be cause for despair, history is replete with structural changes that redefine economic relations—for better or for worse. My goal for the Commission and my work since has been to bring new thinking to the fore, to illuminate possibilities for decoupling growth and prosperity. This kind of re-envisioning can point to a coherent whole, thereby opening doors to structural change.

You have noted the alignment of the Andean concept of “Buen Vivir” with the tenets of post-growth economics. What is “Buen Vivir,” and what can we learn from it?

Rooted in indigenous beliefs, the concept of “Buen Vivir” promotes a way of living based on a mutually respectful, interdependent coexistence between humans and nature. It speaks to the key question of how we define well-being, a question I explored as part of my Commission work under the aegis of the Whitehall Well-Being Working Group. The premise of that group was that if you had a different goal, such as well-being rather than growth per se, you would see the measurement of prosperity and policies to achieve it in a different light. This concept emerged in the UK about at the same time as Buen Vivir became a national political project in Ecuador, although I was not aware of this concurrence.

Years of well-being research have provided important insights into the web of relationships between income and factors such as well-being, education, and life expectancy. This body of work has identified a kind of “sweet spot” that is almost exclusively occupied by Latin American nations, where countries have achieved high levels of well-being at relatively low income levels. Some mix of cultural, social, and political conditions has enabled these countries—many of them small- and middle-income—to decouple prosperity from growth. Chile, Costa Rica, and Cuba in particular come to mind. At this point, I see these examples as a fascinating experiment, but not necessarily replicable in larger countries and in other regions.

You have written that “the moment it stops being permissible to question the fundamental assumptions of an economic system that is patently dysfunctional is the moment political freedom ends and cultural repression begins.” Do you see signs of such repression in today’s political climate?

Yes, I do. What is going on today is largely attributable to the failure of growth-based capitalism. It is perverse to think that we can rescue ourselves from it by a return to a turbo-charged version of the same system, with a little bit of misogyny, racism, xenophobia, and populism added to the mix. I see this as deriving from a systems failure, the same failure I sought to articulate almost a decade ago.

There was a left-wing manifestation of populism in movements such as Occupy that emerged in response to the blatant reward of the architects of the financial crisis with bailout packages while social investments benefitting the poor were cut. Austerity was gradually ripping away the social infrastructure essential to the basic well-being of the poor and middle class, who had been economically and socially left behind. Health care, education, and job security all suffered, and people were forced to look for answers to their dispossession. Unfortunately, some of these people have turned to a right-wing manifestation of populism. In the US, such disillusioned individuals turned to a disingenuous, elitist billionaire. It is paradoxical in the extreme, but culpability lies in a failure to address the structural deficiencies in the existing system. We still struggle to open up debates and minds to the nature of the system, to question the political influences seeking to turbo-charge a failed capitalism that continues to spawn growing inequality. That, to me, is cultural repression—and we should fight against it. In some ways, it comes back to my primary purpose in fostering a post-growth dialogue: to create the political space for this conversation which I believe is one of the most important of our time.

How do you see the link between post-growth economics and what we call a Great Transition, a societal transformation rooted in well-being, solidarity, and ecological resilience?

I see the two as closely connected and mutually enriching. The Great Transition Initiative was created to provide a safe space for exploring global futures, an increasingly important exercise that needs protection during a period wherein hope and imagination are in short supply. As I have watched the evolution of Great Transition writing and dialogue, I am full of admiration for the safe space it has created. However, we must recognize that while this enclave of clear thinking might be very comforting and essential to us as a community, we must avoid too much comfort. We must explore unsafe spaces as well as convene within safe ones. We must bring our conversation well beyond the boundaries of our comfort zone, a challenge that takes hard work and commitment. But without such expansiveness, we will fail to deliver to the world what it most needs—a narrative of change that is powerful, persuasive, and plausible.

Updated 25 April 2017

|